We've chosen these reliable products from these top manufacturers to develop classrooms with the most appropriate delivery of curriculum

so that students will have a meaningful learning experience as they focus on the applications of science and technology .

User References: Metropolitan Community College, Omaha, NE

Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

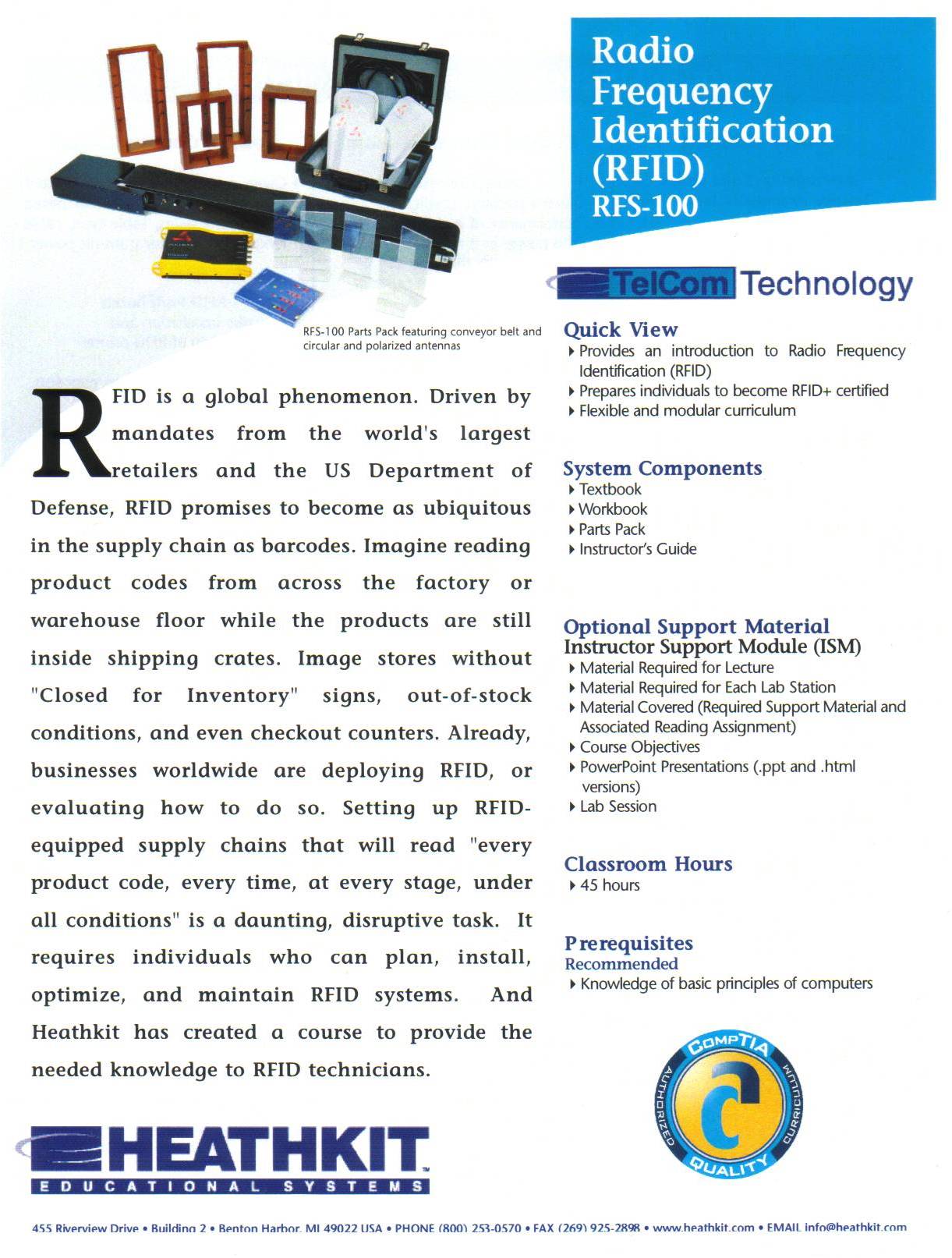

Radio Frequency Identification (RFID)

RFID is a global

phenomenon. Driven by mandates by the world's largest retailers and the US DoD,

RFID promises to become as ubiquitous in the supply chain as

barcodes. Imagine reading product codes from across the factory or warehouse

floor while the products are still inside shipping crates. Image stores without

"Closed for Inventory" signs, out-of-stock conditions, and even checkout

counters. Already, businesses worldwide are deploying RFID, or evaluating how

to do so. Setting up RFID-equipped supply chains that will read "every

product code, every time, at ever stage, under all conditions" is a daunting,

disruptive task. It requires individuals who can

plan, install, optimize, and maintain RFID systems. Heathkit has created a

course to provide the needed knowledge to RFID technicians. Heathkit's

Support materials

include presentation in both .html and PowerPoint versions..

![]()

By Mary Hayes Weier

InformationWeek

![]()

For two weeks last September, fresh spinach disappeared from grocery store shelves. The Food and Drug Administration recalled all spinach after E. coli-tainted leaves sickened hundreds of people.

Using the bar code on a bag of bad spinach, investigators traced its origin to California's Salinas Valley. Then began a painstaking search for the grower, all the while spinach was being pulled from grocery stores, distribution plants, and processing plants and destroyed. A growers' organization estimates the recall cost the spinach industry as much as $74 million.

|

|

|

RFID helps the meat industry figure out where the beef is Photo by Mike Cassese/Reuters |

|

|

|

It would have been much faster to track the contaminated leaves to the grower if spinach bags and containers had carried radio frequency identification tags with complete histories of the contents' origins. RFID tags can hold considerably more data than bar codes and are more easily read because they don't require a line-of-sight connection to a bar-code reader. So what's the holdup? Silicon RFID chips still cost too much. To use them for item-level tagging, they would have to cost less than 1 cent, and considering the required components--an antenna and a microchip--that may never happen.

Get rid of the silicon and RFID could work for the food industry. Fortunately, several companies are developing silicon-free alternatives. PolyIC, half-owned by Siemens, is working on RFID tags made by printing electrically conducting and semiconducting polymers on polymer film. PolyIC recently announced that it has developed a printing process that lets it produce miles of the plastic tags, and it plans to produce 13.56-MHz high-frequency RFID tags this year.

OrganicID, recently acquired by Weyerhaeuser, has invented an RFID tag based on paper, creating circuits through the layering of electronic ink that costs less than a cent. Weyerhaeuser plans to market the tags to the consumer goods and retail industries.

Somark Innovations has developed a nontoxic RFID ink it says can be stamped onto meat. Somark will market its product to the cattle industry, which is being asked to comply with the Department of Agriculture's National Animal Identification System. The agency began working on the national ID system after a cow infected with mad cow disease was found in the United States in 2003. The system, which is expected to be in place in two years, will provide every newborn calf with a 15-digit identification number and will include databases managed by states and industry groups.

The food industry has experience with RFID. Some manufacturers are working to comply with Wal-Mart Stores' pallet-level tagging requirement, for example. And some processors, such as Atlantic Beef Products, are trying new tracking methods. The Ontario beef-processing facility is using RFID to record data on cow carcasses and the resulting cuts of meat as they travel through its processing plant and on to distributors (see story, below).

Item-level RFID tagging has the potential to increase food safety and cut costs in the food supply chain by improving stock management, expanding theft controls, and expediting the retail checkout process. Concerns are rising over food tainted in the supply chain because of sloppy processing practices, and the Department of Homeland Security considers bioterrorism to be among the biggest threats facing the country.

Still, the food industry continues to rely on a bar-coding system that, because of limitations in readability and data storage, provides very little information on where food came from. "To some extent, America is in denial about food safety," says Peter Harrop, chairman of IDTechEx, an RFID research firm. Printed RFID tags, whether on plastic or paper, hold the most promise, Harrop says.

RFID will be on the agenda later this month at the Food Industry Congress in Florida, attended by every big manufacturer. Industry and government officials are discussing the possibility of tagging cases of leafy green vegetables with RFID tags to prevent a repeat of the spinach recall.

Change happens slowly in this industry and has often been in response to a major catastrophe. In 1993, hundreds of people were sickened and four children died after eating hamburgers that hadn't been fully cooked at Jack in the Box restaurants. "It went from a mistake by a $4-an-hour employee to a highly regulated process," says Craig Nelson, founder and CTO of Vigilistics Software, which provides food-tracing technology. "Now charts and records have to be kept in every restaurant to make sure that never happens again."

Change in fruit-juice processing came after unpasterized Odwalla apple juice containing E. coli caused kidney failure in several children in 1996. "Fruit juice was self-regulated until Odwalla. Within weeks, that became a highly regulated industry," says Nelson, who has worked as a consultant to the FDA for almost 15 years, instructing officers on various issues surrounding regulations, manufacturing, and food-industry technologies.

One danger that RFID could help with, Nelson says, is the possibility of a common food ingredient, such as a stabilizer or taste enhancer, getting contaminated at the site of its origin with a substance such as anthrax and then distributed. It could be mixed with a few ingredients at one food plant, sent to another and mixed with more ingredients, and end up at the final manufacturer, where boxes of cake mix or macaroni and cheese are produced. Consider that many processed foods have a shelf life of a few years or more, making it even more difficult to find every contaminated box.

RFID tags could trace the history of every ingredient in a package of food, and RFID readers could scan those tags quickly, getting data into investigators' hands much faster. That capability alone could prevent widespread illness and save lives next time contaminated food ends up on consumers' dinner tables. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

RFID From Farm to Fridge

Atlantic Beef Products, an Ontario beef-processing facility, just won a gold award from a Canadian IT organization for its use of RFID, tracking software, and mobile technologies.

Cows' ears are now tagged with bar codes. Those tags will start to be replaced with RFID tags next month. After the cows are killed, their ear tags are scanned, and a unique record of each animal is entered into Merit-Trax Technologies' database for food traceability. The carcass goes onto two leg hooks, each equipped with an RFID chip. Via a reader, the RFID chips on the leg hooks are synced to each animal's database record.

RFID solves a common meat processing plant problem for Atlantic Beef: To prevent bar-code tags from being contaminated with E. coli on the slaughter floor, they're removed from the carcasses, put into plastic bags, and pinned onto the carcasses once they enter the "clean" side of the manufacturing plant where the meat is cut and processed. Workers who handle bar-code tags and the handheld scanners have to change clothes and shoes when moving to the clean side of the plant so they don't spread contaminants. Since RFID tags don't need to be in a reader's line of sight, they're handled much less, reducing the number of workers needed and the potential for contamination.

The carcasses are split in two and inspected. From that point on, RFID readers and Psion Teklogix's handheld computing devices are used to collect information about each carcass half, including quality of the meat, any instances of degradation to a carcass, and weight. The system lets Atlantic Beef generate invoices quickly; the manual process used to take hours.

Tracking of carcass halves continues as they go into the cutting system, where they're cut into 15 or 20 pieces. Each piece of meat is given a unique ID, in addition to the animal's original ID. Specific cuts of meats are then shrink-wrapped, with identifying information printed onto a bar code. The pieces are then divided by cuts and packed into cases.

Once the meat is unpacked at a distribution point, the trail ends: Pieces are repackaged, and the identifying information is discarded. Still, if Atlantic Beef ever has to issue a recall, it has a record in its database of where every case of meat was sent, who bought it, and information on every animal that went into that case. The system is regularly tested in mock recalls. "An inspector could walk into the plant at any time and want a recall record of all animals killed 15 days ago," says Paul Berry, VP of software development at Merit-Trax Technologies. "We've produced those reports within 10 minutes."

That's not quite traceability from the farm to your refrigerator, but it's a step in the right direction.